January 22, 2018

For most of 2017, the policy debate in Washington centered on Republican proposals to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA). After much drama, Congress failed to enact a health bill. Nonetheless, it succeeded in effectively repealing one provision, the individual mandate, in the new tax law. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the number of uninsured Americans will increase by 13 million and individual market premiums will rise 10 percent as a result. The repeal of the individual mandate comes after a number of other actions by the Trump administration that limit consumer protections and opportunities for enrollment and increase premiums for middle-class consumers.

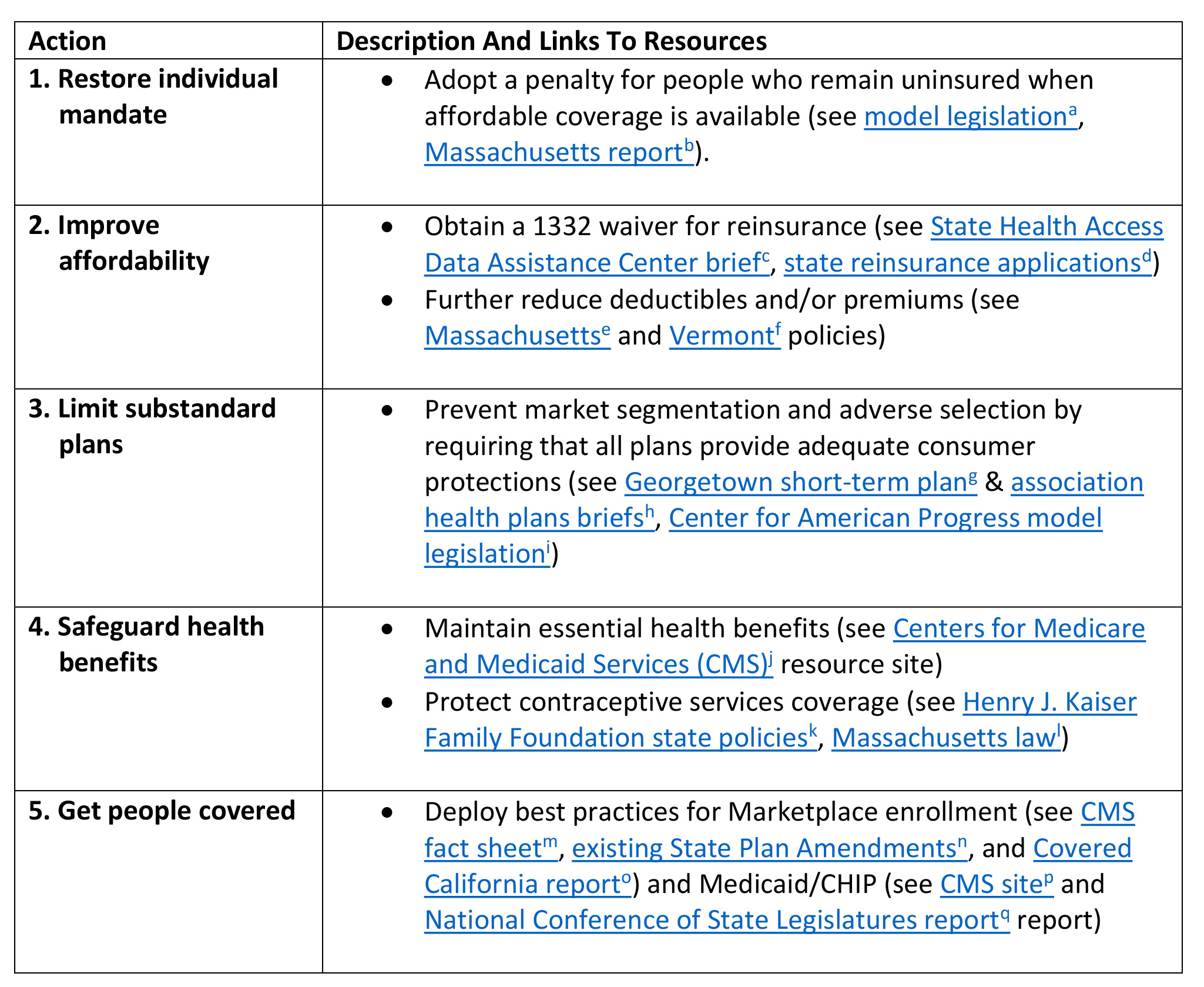

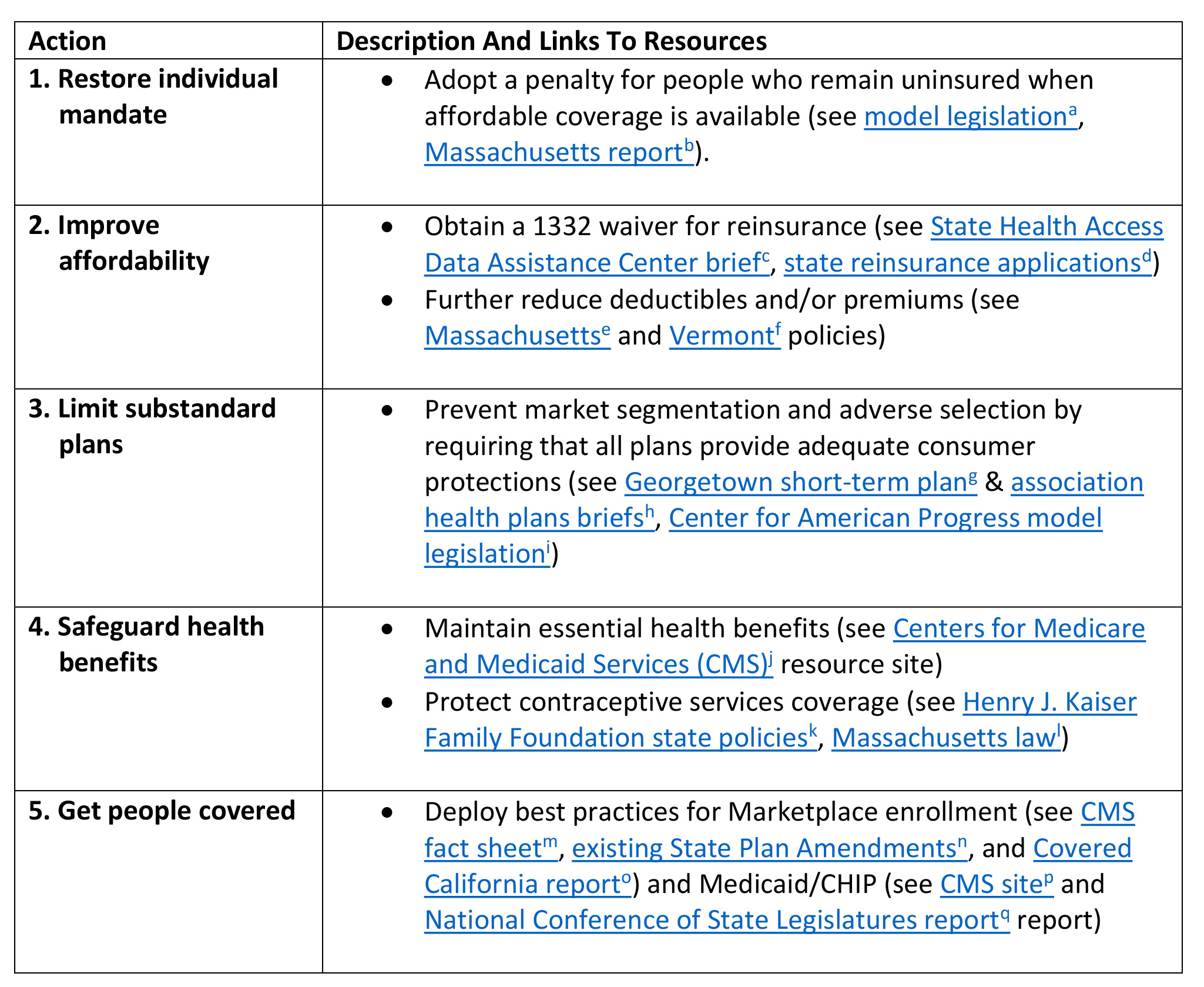

Here, we outline five actions states could take in 2018 to mitigate the damage done to the individual health insurance market by federal legislation and executive actions (see Exhibit 1). They are in addition to steps many states have already taken (e.g., directing insurers to reflect the cessation of cost-sharing reduction payments solely in premiums for silver plans and working with insurers to ensure coverage is available in all areas). While other options could (and should) be considered by states, we believe that these five are likely to be particularly effective and feasible for states to implement on a short timetable.

Source: Authorsf analysis. Note: amodel legislation; bMassachusetts report; cState Health Access Data Assistance Center brief; dstate reinsurance applications; eMassachusetts; fVermont; gGeorgetown short-term plan; hassociation health plans briefs; iCollege of American Pathologists model legislation; jCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); kHenry J. Kaiser Family Foundation state policies; lMassachusetts law; mCMS fact sheet; nexisting State Plan Amendments; oCovered California report; pCMS site; qNational Conference of State Legislatures report

The tax legislation Congress enacted in December zeroes out the penalty associated with the individual shared responsibility provision of the ACA, also called the individual mandate, starting in 2019. This penalty is paid by individuals who have access to affordable minimum essential coverage but were uninsured for three months or more in a year. The amount, which starts at $695 per year for an adult, is tied to income and capped at the national average bronze premium.

The tax legislation removes this important tool for increasing insurance coverage. The tax penalty discouraged people from gfree ridingh by waiting until they needed health care to buy insurance, thereby avoiding paying premiums while they were well. This behavior raises premiums for people who remain insured. In addition to these direct incentive effects, the requirement to have coverage raised awareness and contributed to increased enrollment in private plans and Medicaid, even in states that did not expand the program under the ACA. Eliminating the mandate will also create near-term uncertainty for health insurance companies in setting premiums for the individual market, which may cause some of them to exit the market.

To address this problem, states could restore the ACA individual mandate by creating a penalty at the state level to replace the one zeroed out by the tax bill. States could generally rely on existing federal rules, thereby providing continuity for stakeholders. States could also incorporate changes to the federal rules to meet their specific needs or, as Massachusetts did, enact their own vision for an individual mandate.

This action would help keep private health insurance premiums from rising and prevent a reduction in insurance coverage. The federal government would bear the cost of premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions for people remaining in the Marketplace and most of the cost of higher Medicaid take-up. States would collect revenue from mandate penalties and save on uncompensated care programs, Moreover, if a state has already budgeted for current Medicaid and Childrenfs Health Insurance Program (CHIP) levels of coverage (without taking into account repeal of the federal mandate), then maintaining the higher take-up should have no additional cost. No federal approval would be required for this proposal. States considering state Innovation (1332) or Medicaid (1115) waivers probably should restore the individual mandate first. This would avoid the need to overhaul their waiver applications later and provide more flexibility by maintaining baseline federal spending, making it easier for some waivers to meet the test of not increasing federal budget deficits.

Some observers have suggested that, rather than reinstating an individual mandate, policymakers should explore alternatives, like continuous enrollment surcharges or gdefaulth enrollment. But these alternative approaches would be less effective than reinstating an individual mandate. CBO has estimated that continuous enrollment surcharges would actually reduce insurance coverage; in any case, such a policy would likely violate federal law and thus could not be enacted at the state level. Similarly, default enrollment is incredibly complex and likely unworkable even at the federal level; the operational challenges would be even more severe for states.

In addition to the individual mandate repeal, the Trump administrationfs policies related to the ACA have increased premiums, particularly for middle-class consumers who do not receive tax credits to help them with premium costs. Without the Trump administrationfs actions, analysts have estimated that premium increases for 2018 would have been in the single digits.

States could obtain a state Innovation Waiver from the federal government (also called 1332 waivers) to establish a reinsurance program to lower premiums, offsetting increases due to the mandate repeal and other federal actions. Reinsurance pays for a portion of claims for the most expensive enrollees, allowing insurers to set lower premiums. Alaska, Minnesota, and Oregon applications for state Innovation Waivers reinsurance programs have been approved (see state applications). These applications are relatively straightforward, with potentially the greatest challenge being securing funding and enacting state authorizing legislation. Given the initial application deadline for 2019 plans of June 20, 2018, state legislation and applications for waivers would likely need to be secured and submitted in the first quarter of the year.

People eligible for premium tax credits do not significantly benefit from reinsurance because the tax credits generally shield them from the effects of premium changes. To assist these consumers, states could, for example, provide supplemental premium assistance. Additionally, they could further lower deductibles for enrollees with income below 400 percent of poverty by providing supplemental cost sharing assistance, as Massachusetts and Vermont currently do. States that run their own Marketplaces can implement such programs by enrolling individuals in supplemented coverage at their initial enrollment. However, even states that operate on the federally-facilitated Marketplace have options. They could reimburse insurance companies directly for providing lower cost sharing or premiums to eligible enrollees or provide state tax credits that reimburse individuals after the benefit year has concluded, as Minnesota has done for unsubsidized enrollees. Such programs could be funded by states or potentially through State Innovation Waivers that produce federal savings.

The Trump administration has, in a number of ways, promoted the sale of health plans that do not provide the ACAfs consumer protections. President Donald Trumpfs October 12, 2017 executive order called for expansion of the use of short-term plans. Such plans can deny payment of claims or coverage for people with pre-existing conditions; charge such individuals or older American unlimited premiums; exclude key benefits like drug coverage or maternity care; and have high deductibles and low annual limits on what the plan pays for care. Additionally, the Trump administration extended the use of transition plans and aims to loosen rules for grandfathered plans – both of which lack the ACAfs consumer protections. The executive order also called for the expansion of association health plans (AHPs). Recently issued proposed rules would permit AHPs to sell coverage to small businesses and self-employed individuals that omits many of the ACAfs consumer protections.

All consumers have the potential to be harmed by the expansion of substandard plans. Though those who enroll in these skimpier plans may pay lower premiums, many will find they have inadequate coverage when they need it. For example, the New York Times reported that a short-term plan denied payment (grescinded coverageh) for a $900,000 bill for a triple bypass surgery because the enrollee failed to disclose alcoholism and degenerative disc disease – conditions for which he was never diagnosed. AHPs have also sometimes been a conduit for fraud. For example, an AHP marketed to churches and small businesses in South Carolina diverted $970,000 in premiums to the owners, while leaving $1.7 million in unpaid claims. Meanwhile, those who stay in ACA-compliant health plans, a group that will include many people with significant health care needs, will pay more for the same coverage as healthy enrollees are diverted into substandard plans.

States could, most simply, require that the ACA consumer protections apply to all fully insured health plans sold to individuals, including, for example, short-term limited duration plans. By creating a level playing field, this approach would undo the harm from the Trump administration proposals as well as prevent new types of substandard plans from cropping up through unforeseen loopholes. While a comprehensive approach would be most effective in safeguarding the statesf insurance markets, states could also consider narrower approaches. For example, they could extend ACA rules to short-term limited duration plans or other specific categories of currently exempt plans. Or state laws or regulations could limit the duration of short-term limited duration plans, prevent renewals, and/or apply certain consumer protections to them, an approach that national insurer associations have supported. States could also require AHPs to comply with key consumer protections and financial standards.

Blocking expanded sales of these types of policies would lower premiums for ACA-compliant plans. This would reduce costs for individual market enrollees not receiving premium tax credits and would lower federal costs by lowering premium tax credits. It is possible that a state could reinvest such savings in health coverage through gpass-through paymentsh under a 1332 waiver. In order to do so, a state would need to make its law or regulation blocking the expansion of short-term plans contingent on approval of its 1332 waiver (for example, a state could adopt a policy change immediately, but make its continuation for future years contingent on the waiver). A state could use the pass-through funding to support health coverage, for example to fund or partially fund supplemental financial assistance, as discussed above.

The proposed 2019 Benefit and Payment Notice includes a number of changes that weaken standards for essential health benefits that apply to most individual and small group market plans. If finalized as proposed, a state could, for example, allow insurers to substitute benefits from one of the ten statutory categories for another. A state could also create its own benchmark plan rather than using one already in use in the group market, potentially dropping or severely limiting items and services within a benefit category. Additionally, the Trump administration separately issued rules to immediately allow employers with religious or moral objections to block ACA-required coverage of contraceptive services for workers. While these rules were recently enjoined, the Trump administration will likely continue to pursue this policy.

Because of upward pressure on premiums from the repeal of the individual mandate and federal actions with similar effects, states may feel pressure to limit benefits to reduce premiums. This puts people with pre-existing conditions at risk of losing access to needed benefits and paying more out-of-pocket for their health care, as they did prior to the ACA. And, should the Trump administrationfs roll-back of contraceptive coverage be upheld, experts suggest that the consequence would be an increase in unintended pregnancies.

Once the 2019 Marketplace rule is finalized, states should review their essential health benefits and state benefit requirements to ensure they are sufficient. States may not need to take action, depending on the final rule, but should be prepared to limit the impact of federal policy that allows insurers to go beyond state-authorized flexibility in benefit design. Similarly, while the recent court injunction prevents employers from dropping contraceptive coverage, states like Massachusetts have implemented their own requirements that protect against the effects of the potential federal policy change (see its law).

In addition to repealing the individual mandate, which is projected to reduce insurance coverage by 13 million, the Trump administration has used executive actions to limit enrollment in the Marketplaces. These actions include, but are not limited to, cutting in half the 2018 open enrollment period, drastically cutting funding for marketing and Navigators, and erecting enrollment barriers such as excessive verification of eligibility for special enrollment periods. While HealthCare.gov enrollment through December 15, 2017 surpassed expectations, final enrollment for the Marketplaces is still likely be less than it was in 2016 and 2017.

The Americans most likely to fall out of the system due to these actions are those who are young, have limited health care needs, or for whom the cost of signing up (e.g., time taken to figure out how to enroll, gather required documentation) exceeds the perceived benefit. These enrollees will have reduced access to preventive care and other services and decreased financial security, and their exit from the insurance market will increase premiums for those who remain

To help prevent projected reductions in insurance coverage, states could increase the opportunities for and ease of signing up for coverage in the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP. State-based Marketplaces are well positioned to fund and adopt best practices on education, marketing, and in-person assistance for the Marketplace. A recent report from Covered California documents its best practices and estimates that those actions substantially lowered premiums. The HealthCare.gov experience suggests effective strategies include using targeted media (e.g., YouTube, Facebook, optimized search), reaching out close to deadlines, and explaining why coverage matters. States using HealthCare.gov may also consider these kinds of strategies. These activities may require additional funding, which could be raised through Marketplace insurer user fees, but would likely not otherwise necessitate state legislation.

All states can consider a variety of tools to promote awareness of the individual market among consumers likely to be eligible. States can promote the Marketplace among those eligible for state unemployment benefits, other public benefits with higher income limits (like those with SNAP categorical eligibility), and through divisions of motor vehicle offices, community colleges, and schools. States may partner with prominent local companies or stakeholders like hospitals to develop creative strategies adapted to their market. States can also ensure that anyone disenrolled from Medicaid receives assistance in enrolling in a Marketplace plan, and may offer similar assistance to the parents of children enrolled in CHIP.

Equally important is increasing Medicaid and CHIP enrollment: CBO projects 5 million people could lose coverage in these programs due to the mandate repeal. States could take actions to streamline eligibility. These include but are not limited to:

Most of these actions could be adopted through State Plan Amendments rather than Medicaid 1115 waivers. While increasing coverage increases the state share of costs, these costs may be built into a statefs pre-individual mandate repeal baseline, since these activities would help to maintain coverage that would otherwise be lost.

This gold-standard package would expeditiously promote affordable, stable health coverage – which is at risk given actions taken by the Trump administration and Congress. Of course, states may want to take further action in some areas. But the effective, targeted policies we describe here offer states a clear path to use their significant control over their individual insurance markets to make those markets work well.